How I Created my Interactive, Real-Time Chess Game

If you haven’t noticed, if you go to chrisnun.es on a desktop computer, there is a big chess board floating up and down. If you click on the board, you have the option to challenge me to a chess game, which can be played out in real time!

Conveniently, if you don’t have the time to sit down and play a full game of chess, the website will save your progress and we can resume the game later. At the time of writing this, I have received a few anonymous challenges through the website, but not one person has followed up and played a game 😔.

This post will give a high-level breakdown of how I created this real-time chess game, in case any chess fans are inspired (😩) and want to do something like this on their own.

Background

I have always been pretty into chess! I learned how to play in high school and ended up founding a chess club in my senior year. I took a multi-year break from the game in college, until my passion was re-ignited by The Queen’s Gambit.

Around the same time, I was redesigning this website and I was in search of something cool/fun/quirky that I could feature on the homepage. This redesign happened to coincide with my rediscovery of chess, so the chessboard seemed like a natural thing to feature on the site.

From there, it was a natural move to have the game be interactive between myself and website users. After dismissing the idea of a chess A.I. that played at my level (because that is hard), I settled on having the website create a game that I could respond to on my phone.

The Idea

I wanted this interactive chess game to function the same way that a normal online chess game would. If you have ever used Chess.com, Lichess, or any other chess website or app, you are probably pretty familiar with the flow of events.

Generally, the first player sends a challenge to the second player, who has the option to accept or decline the challenge. If the second player accepts the challenge, then the game is created and they begin to play. If the second player declines the challenge, then no game is created and the first player has to send a new challenge to try again.

In this scenario, the website visitor acts as the first player and sends a game challenge to my phone. As the second player, I accept the games and play them on my phone, while the first player plays through the chessboard on the website.

Tech Stack

There were a few different libraries/tools that I used in creating the game, mainly:

- chessboard.js — Provided the chessboard UI

- chess.js — Handled chess logic, mainly determining legal/illegal moves

- Lichess Board API — The big one. Was used to communicate game state between my phone and the website

- NodeJS w/ Express — Used as a medium between the Lichess API and the frontend client

The most important one of these was the Lichess API, as it allowed me to communicate moves back and forth between the web client and my phone. The chess games are played through the Lichess service, and the Lichess API is what sends game updates to the frontend.

The actual structure of the program is bigger than it would seem, so I’m going to devote an entire mini section to it.

Structure and Flow

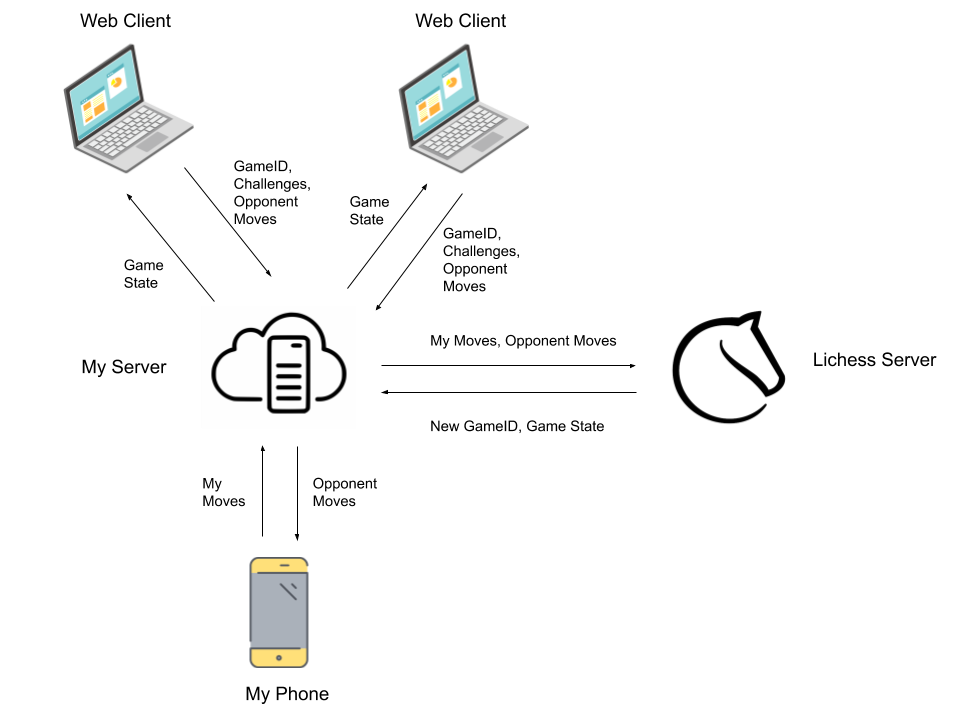

Here is a cheesy clip-art diagram of how the game is structured and how the data is passed around:

In case that diagram was horribly uninstructive, here is a more detailed breakdown of each component of this system.

My Phone

This part is pretty simple. I have an account on Lichess.org, and whenever someone goes to my website and creates a new game, I get a notification from the Lichess app that says "chrisnunes_website has challenged you to a game".

From there, I just play the game out through that app just as I would any other game. From my perspective, it is as if I am playing a Lichess user named chrisnunes_website.

The Lichess API

The Lichess Board API is what allows me to create the abstraction of a simple chess game for both myself and the client. To the client, it seems like they are simply playing chess against some online opponent, and for me, it seems like I am just playing a normal chess game on my phone. Thanks to the Lichess Board API, both of these can be true.

The Lichess Board API allows you to programmatically control the actions of a Lichess user, such as creating challenges, sending chat messages, and making moves in a game. To take advantage of this, I created a Lichess user named chrisnunes_website that acts as a proxy for the user playing through the website.

This means that whenever a user sends me a challenge through the website, the chrisnunes_website user on Lichess is really sending me a challenge. And whenever the user is making moves in the game, it is really chrisnunes_website sending me moves under the hood.

In essence, each game played on this site is actually a Lichess match between the users chrisnunes_website (the web user) and chrisnunes (me). I control the chrisnunes user through my phone, while the web client and the game server combine to allow the web user to control the chrisnunes_website user.

The Game Server

This is the messenger between the client and the Lichess API. All of the requests to the Lichess API require an authorization token, which I didn’t want exposed on the frontend. So, I created a game server to act as a go-between and make the authorized requests in private.

This server sends and receives data with both the client and the Lichess API. From the client, the game server receives requests to create new challenges, as well as moves the user makes in existing games. Whenever the game server receives these messages from the client, it passes them along to the Lichess API with the proper authorization.

The server is also constantly listening for new game events or updates from the Lichess API. For example, the Lichess API will send moves from my phone to the game server, or send updates about challenges being accepted or declined. In both of these cases, the game server will once again just forward the messages to the client.

The Client

Finally, the client. In this game, the client is synonymous with the website, or the web browser that the user is using. The client is responsible for communicating game moves with the game server and updating the chess interface for the user.

The client will always be listening for the game server to send it information about new moves, and it will send the game server messages of its own whenever the user makes a move or creates a challenge. The client also utilizes the browser local storage to track any ongoing games the user has. That way, when a user opens the page, the client can immediately know whether there is an existing game for this user or not.

The second function of the client is to update the graphical interface that the user sees. The board is rendered using chessboard.js, and whenever the game server sends the client a new move, the client updates the chessboard accordingly.

The third function of the client is to provide the user a way to interact with the game. However, the drag-and-drop chessboard provided by chessboard.js does not have chess logic included with it by default. So, we use chess.js to validate moves that the user makes and ensure that they are legal. If the user makes a legal move, the client will send it to the game server, which will in turn use the Lichess API to send it to my phone.

Recap

To put it in simple terms: we have a client that the user can interact with to play the chess game. The client sends and receives messages from the game server, which in turn uses the Lichess API to send and receive messages from me, playing on my phone.

These four components all work together to create a simple effect: a user and I can both be playing the same chess game, at the same time, through two unrelated mediums.

Something Cool: ndjson

Whenever I have worked with realtime applications in the past, I have used tools like Google’s Firebase Realtime Database and React to handle the realtime updating for me. This was the first project I have done that used neither of these tools, so I had to learn how to create this realtime effect on my own.

In the end, my solution was to stream ndjson, or “Newline delimited JSON”. From a server/sender perspective, this was pretty similar to how you normally send responses. The difference is, with streaming data you can send multiple responses to the same request.

For example, in Express, this code would stream an infinite amount of numbers in response to a request:

app.get('/numbers', (req, res) => {

res.setHeader('Content-Type', 'application/json')

let num = 1;

setInterval(function () {

num++;

res.write( num + "\n");

}, 100)

})

This is similar to how you would send a normal response, but in this case we use res.write() to send multiple responses. Normally, you would use res.send() to send a single response.

However, from the client/receiver’s point of view, it is significantly different. For static data, getting data from an API request and accessing it could be as simple as:

const response = await fetch("chrisnun.es/numbers");

const data = await response.json();

console.log(data);

However, with streaming, you have to worry about constantly listening for new data and processing it. The basic structure is to set up a reader for the endpoint that will always be listening for new data to be sent, like so:

const response = await fetch("chrisnun.es/numbers");

const reader = response.body.getReader();

let result;

while (!result || !result.done) {

// listen for more data

result = await reader.read();

// data is sent as a Buffer, so we must convert to text

let content = new TextDecoder("utf-8").decode(result.value).trim();

if (content)

console.log(JSON.parse(content));

}

Even though it made my code more complicated to write, it was really rewarding to figure out a new way of streaming data that is honestly really easy to use. I think in the future I will definitely use streaming to reduce the size of my API calls and implement real-time applications.

Conclusion

This chess game was really fun to build, and I honestly learned a lot from going through the whole development process. Unfortunately, the game is still pretty untested, and there are probably a lot of bugs to clean up in the gameplay. For instance, I have no idea what will happen if the computer user tries to promote a pawn. I don’t even know if they can. The thought keeps me up at night.

But all in all, I am really happy with how this project turned out, and I think that it was a smashing success. Shoutout again to the Lichess team for putting out great APIs and developer tools, I hope that one day the Chess.com team can do the same! (😳)

If you want to test out the game, follow the link below and start a game from the homepage! If I don’t respond, I am likely either busy or asleep. BUT, you can come back and check periodically to see if the challenge has been accepted!

That’s all for now, be prepared for more great content in the future!