Touchy Feely

Touchy Feely - Using Haptic Emojis to Represent Emotions in Instant Messaging

Introduction

The following article is a research paper that I wrote with my friend Levi Villarreal. The paper was a final project for the DH2670 3D Haptics course at KTH Royal Institute of Technology while we were studing abroad.

Authors:

Chris Nunes - chrisnunes57@gmail.com

Levi Villarreal - villarreallevi@utexas.edu

Abstract

While modern instant messaging technology gives us tremendous communication capability, it is ineffective at communicating emotions and feelings when compared to in-person communication. Touchy Feely is a study in communicating emotions through haptic feedback to enhance the quality of digital communication. This project hopes to benefit users with impaired emotional perception by allowing the sender to transmit ’Haptic Emojis’ along with their message, thus removing any ambiguity from the meaning of their words. Through this study, we found that Touchy Feely allowed users to have a greater understanding of the intended emotion behind text messages, and it also gave us insight into the different ways people can interpret haptic patterns, and what they expect a haptic emoji to feel like.

Introduction

The rising popularity of instant messaging has shown that problems can emerge when chat platforms are used as a replacement for face-to-face communication. The question we sought to answer was whether haptic feedback can enhance the communication of emotions in instant messaging in an intuitive and unobtrusive way. Our solution to these problems is to provide an intuitive and simple to use instant messaging app. This app, Touchy Feely allows users to send and receive text messages, much like you would in any popular chat application. However, when a message is received, the phone plays a haptic pattern that communicates the emotion specified by the sender. These ’Haptic Emojis’ lead to recipients of messages being able more to clearly understand the intended emotion, and senders of messages being able to easily achieve their desired sentiment.

This solution will benefit users of any background but has the potential to be especially beneficial to users with impaired emotional perception or users with a non-fluent proficiency in the language that they are using. Users from the first category could be those with cognitive impairments or mental illnesses such as major depressive disorder that cause impaired emotional perception [8]. Users from the second group could be immigrants who are afraid to communicate in a new language due to fear of making an unintentionally offensive statement.

Background

As we will discuss in this section, it has been well-documented that there are notable shortcomings related to virtual communication technology when compared to face-to-face communication. However, as such technology has become more prevalent in the past few decades, there have many attempts to construct tools to circumvent the failings of current technology. While many of these attempts implement similar ideas to Touchy Feely, a large difference is that these solutions use specialized haptic hardware, while Touchy Feely uses an iPhone. Modern iPhones still have complex haptic capabilities but are much more accessible and feasible on a large scale than specialized devices.

Virtual Communication

In the modern era, a majority of communication is becoming digital and is being done through mediums such as phone calls and instant messaging [10]. Not only is instant messaging being used for mundane and daily conversation, but it is increasingly used as a means to communicate profound thoughts and feelings with other people. While instant messaging technology has given us the incredible ability to connect with others who are not physically with us, it is important that we consider and address the drawbacks of this method of communication.

A study by researcher Albert Mehrabian [4] declared that there were essentially three components to face-to-face communication: tone, body language, and the words that are spoken. This research also showed that when emotions and feelings are being communicated, 93% of the speaker’s meaning is conveyed through implicit and nonverbal feedback, specifically tone and body language. However, these two critical parts of face-to-face communication are missing from instant text messaging, which can lead to anxiety and uncertainty about how a message will be received [7].

Existing Solutions

One of the first studies to attempt to more effectively and explicitly communicate emotions in text-based messaging was conducted at the University of Tokyo [12]. The chat system used physiological sensors to determine the users’ current state of emotion and showed that emotion via specific text animations. Rather than the user explicitly sending their emotion, it was determined automatically using devices such as a pulse monitor. This approach found that participants could use such an emotion-based system to communicate more efficiently with each other.

Another approach to emotion-based research involves using natural language processing to extract the emotion behind a text message, rather than receiving the emotion directly from the user. This approach was used in a real-time chat application [5], which found that the approach could be used to determine the sentiment behind a text message with fair accuracy, but not so good as to be a permanent replacement for explicit user emotions.

A haptic related approach to enhancing text communication is iFeel IM [11]. This device and its paired application were able to identify one of nine emotions in a text message, using similar natural language processing methods as the previous study. Different devices were used to present these emotions in a non-intrusive way to the user, namely a vibrotactile belt, and temperature altering devices. By using these devices the researchers were able to simulate the feeling of a hug, tickling, and warming up or cooling down. This approach was found to encourage more empathy in users, as such direct and intimate feedback often caused a much stronger reaction than just text. However, this study used devices that were both bulky, expensive, and uncommon, which is not desirable if such a solution were to be implemented on a larger scale.

Haptics in iOS Devices

Apple has been a pioneer in the field of mobile and wearable haptic technology, in large part due to the scale and widespread use of devices such as the iPhone, iPod, and Apple Watch. In order to facilitate more complex haptic patterns, Apple recently released Core Haptics [1], which allowed for fully customizable haptic patterns. This development feature, available on the iPhone 7 and up, allows for fine-tuned haptic adjustment using the parameter of sharpness, and timing. Method

The methodology of this study was comprised of 3 primary components. First was the development of the chat app itself and ensuring that the app would behave like many of the most popular modern mobile chat apps. Secondly, we designed the haptic patterns that would represent each specific emotion, which involved some trial and error as we revised the patterns based on user feedback. And finally, we devised a system in which we could test users and observe the feasibility of Touchy Feely as a messaging app.

Method

The methodology of this study was comprised of 3 primary components. First was the development of the chat app itself and ensuring that the app would behave like many of the most popular modern mobile chat apps. Secondly, we designed the haptic patterns that would represent each specific emotion, which involved some trial and error as we revised the patterns based on user feedback. And finally, we devised a system in which we could test users and observe the feasibility of Touchy Feely as a messaging app.

Application Development

In order to consider the feasibility of using a chat app such as Touchy Feely on a large scale, we made it a goal to create a chat app with an intuitive user interface, to mimic the look and feel of some of the most popular chat apps used today. To implement a good user interface, we used Swift UI [3] which is a library available to be used with the Apple development environment Xcode. Swift UI provides standard user interface components that are used in many iOS apps, including Apple’s own messaging app. These components were used to provide a sense of familiarity to users and sought to make the user experience similar to one found in any other messaging app.

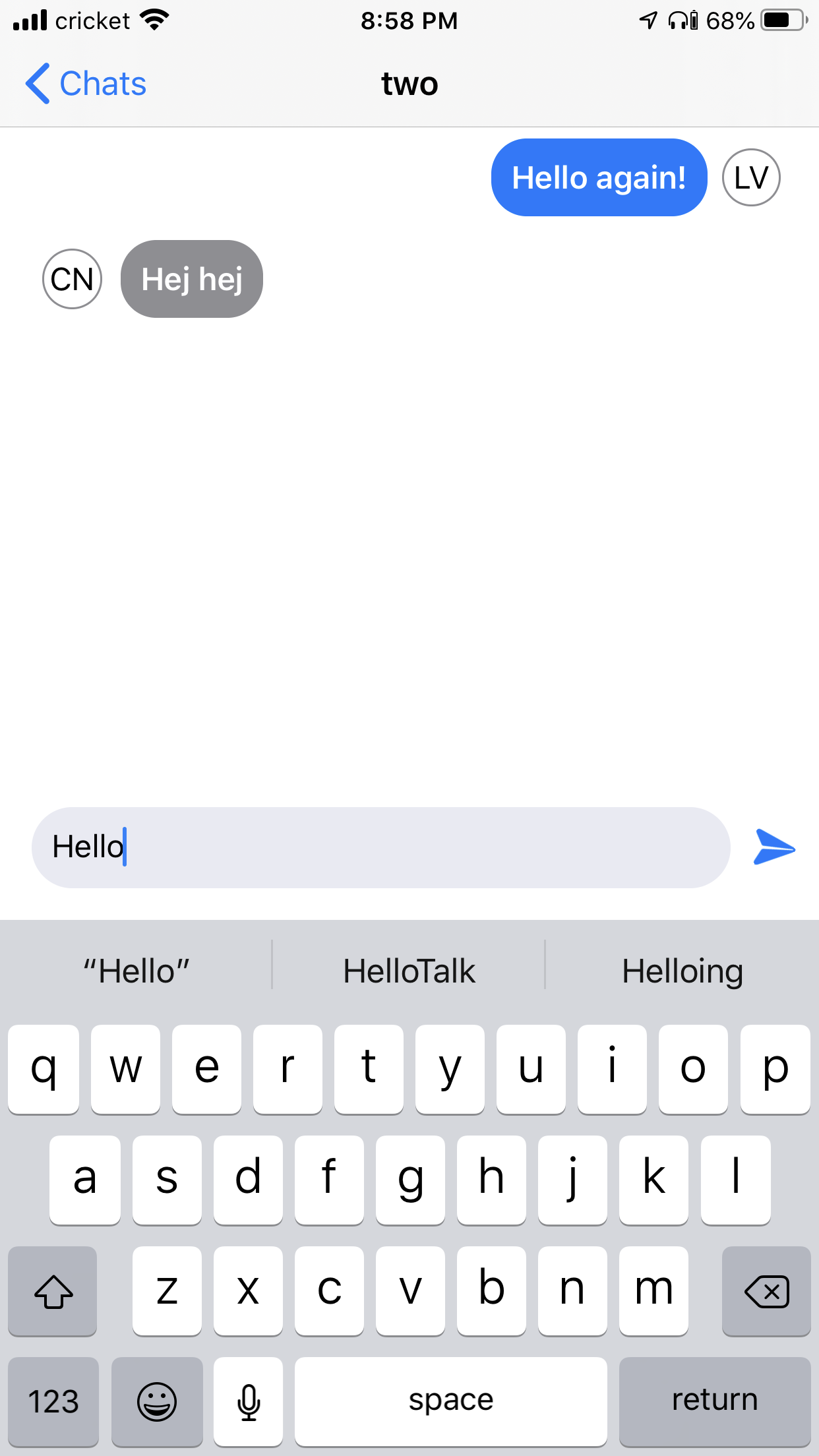

The view of a single chat

To facilitate real-time updates of chats, as well as allow for any number of users to store and retrieve messages, we used Google Firestore [2]. This service allowed for a simple implementation of a real-time database that could handle many users sending and fetching messages simultaneously, without any serious lag. This also facilitated the ability for chats to automatically update with each new text, without the need to refresh or restart the application.

Haptic Representation of Emotions

Designing a haptic representation of emotions required a large amount of prior research and planning. One source used when considering the design of the vibrotactile patterns was Paul Ekman’s research into universal facial expressions and emotions [6]. This research proposed that humans shared five universal emotions: Anger, Sadness, Fear, Enjoyment, and Disgust. Not only did this research provide insight into universal emotions shared by humans, but it also provided insight into how emotions varied in intensity across a spectrum. For instance, outrage and annoyance are both emotions that fall under the ”anger” category, but there is a large difference in the intensity with which we feel these emotions.

This research led us to use three main components in our haptic feedback: intensity, sharpness, and pattern. Intensity refers to the force with which the phone vibrates. We used intensity to differentiate between emotions that naturally have vastly different levels of intensity, such as anger and sadness. Sharpness refers to the feel, or texture, of the haptic feedback. For instance, a vibration that is not sharp will feel like a dull buzzing in your hand, while a very sharp vibration will feel very intense. We used sharpness to differentiate between emotions that would have similar intensity but different levels of sharpness, such as surprise and fear. The final component of our haptic feedback was the pattern, which refers to the actual shape and timing of the haptic curve. As you will see in the following examples of our haptic feedback, the pattern was used to give personality to each bit of feedback and differentiate between very similar emotions.

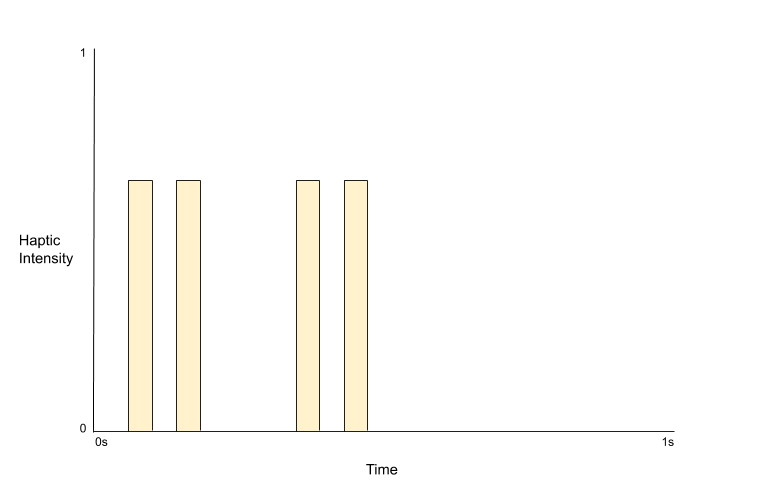

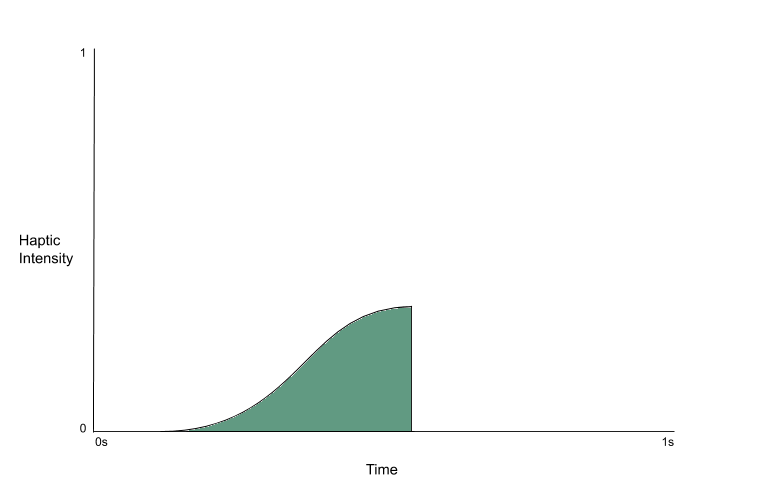

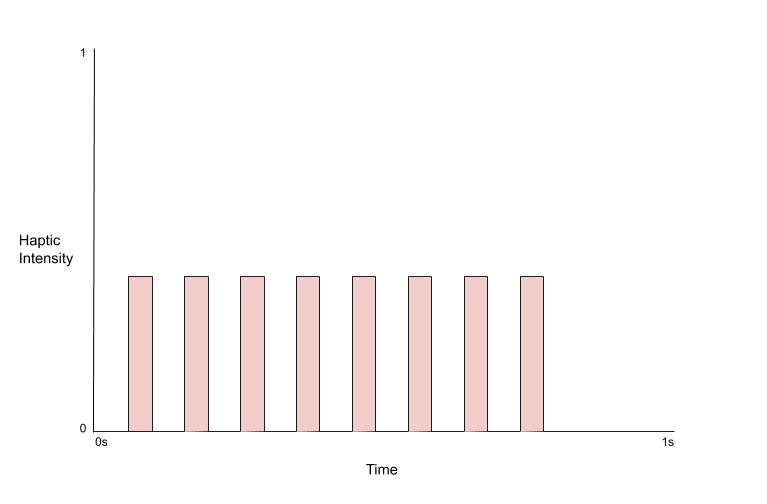

Graph of haptic feedback for "Surprise"

The graph shows the intensity of our haptic feedback over time. The y-axis works on a scale of intensity from 1 to 0, where 0 represents no vibration at all, and 1 is the maximum vibration setting on the phone. The x-axis represents the time that each haptic emotion took to play, with a maximum length of 1 second.

The emotion represented in The above graph is that of surprise. This emotion was not one of Ekman’s five original universal emotions, but we felt like this sentiment was used commonly enough in digital communication to warrant inclusion in the first iteration of this project.

Much like the pattern for happiness, we use bursts of vibration to convey excitement. Unlike happiness, however, we use fewer, more intense bursts. This is to intensify the feeling of excitement and amplify the impact of each burst.

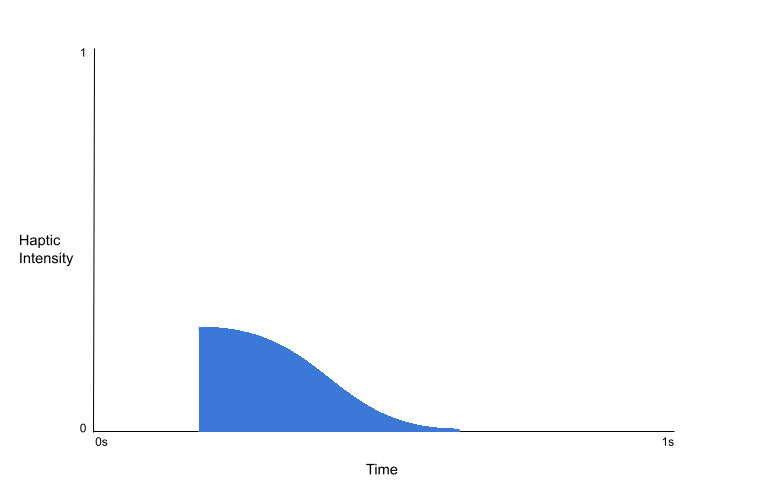

Graph of haptic feedback for "Sadness"

This emotion is sadness. This pattern is the opposite of Figure 6, which was disgust. That is because the two emotions are very similar in both intensity and sharpness. The only real means to differentiate between the two was by modifying the pattern.

The rationale for designing this pattern was that, unlike disgust, which starts slow and eventually grows, sadness is initially more intense and fades over time. The sadness pattern uses the same intensity as the disgust pattern but is slightly less sharp. This, in combination with the reversed pattern, makes it possible to differentiate between the emotions.

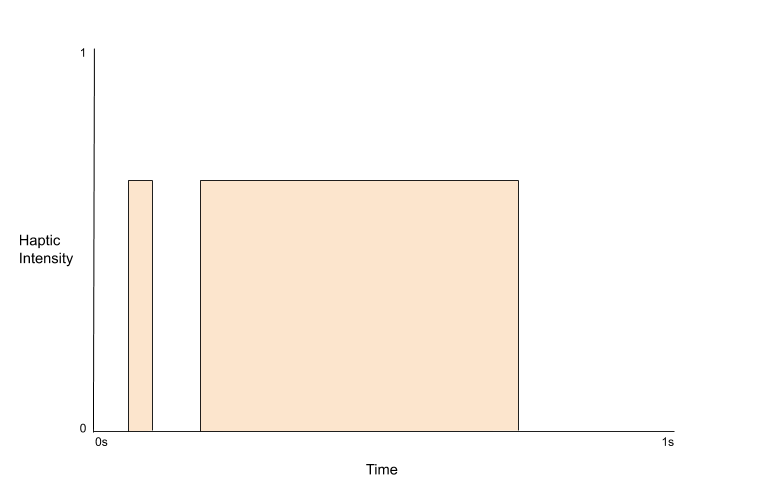

Graph of haptic feedback for "Anger"

The haptic pattern in Figure 4 corresponds to the emotion of anger. Anger is conveyed through high intensity and high sharpness to appear more aggressive than other feedback. The pattern for anger is also designed to convey aggression. The intensity and sharpness combine to create force that is much stronger than that of other emotions, and the sustained vibration is sharper than any other emotion.

Anger has the highest intensity of any haptic feedback that we programmed and is one of the sharpest. This was done deliberately in an attempt to simulate a large range of haptic feedback. In order to have a diverse set of feedback, there needs to be an emotion with very low intensity and an emotion with very high intensity.

Graph of haptic feedback for "fear"

This emotion is fear. Fear is often described as the most basic emotion because it is simple, instinctive, and primal. For this reason, we designed it to have a simple, heartbeat-like pattern.

The pattern was initially designed to have a small amounts of oscillation, as inconsistent patterns give users a feeling of unease. However, it was difficult to vary the vibration pattern in such a small way without users misinterpreting the pattern.

In the end, fear was represented as an emotion with more intensity than low-intensity patterns like sadness and disgust, but less intensity when compared to something like anger. Though it is not a very intense emotion, it was given a large sharpness value, which adds a little edge to the sensation.

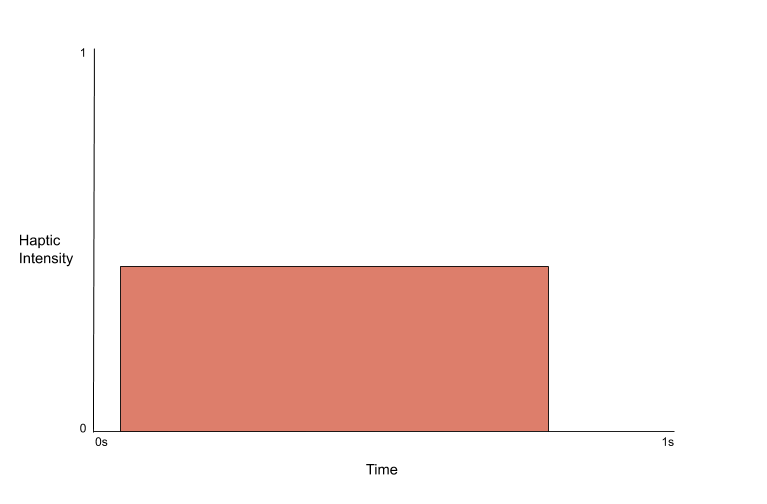

Graph of haptic feedback for "Disgust"

This emotion is disgust. Though disgust and anger are closely related in real life, there is a clear difference between the haptic feedback for each emotion. The haptic pattern for disgust starts out at a low intensity and sharpness, then uses an elliptical curve pattern to grow into a stronger ending.

The feedback for disgust was intended to be similar to the pattern of anger, but less intense and less sharp. To do this, we included a final vibration strength similar to the one used in the anger feedback, but instead of a sustained vibration, we use an elliptic curve to slowly grow into the stronger feeling.

Graph of haptic feedback for "Happiness"

The sixth and final emotion, is happiness, or enjoyment. This haptic pattern is different from the most other patterns, as it consists of four distinct and discrete bursts of vibration with very short pauses between them.

This specific pattern was chosen to convey excitement. It was created with a medium-strong intensity and not much sharpness, so even though the pattern is fast-paced and intense, it does not appear aggressive. One of our testers said that this pattern reminded them of a human laugh.

Throughout the process of designing these haptic patterns, we changed and refined the parameters of each emotion based on user feedback. Our goal with these patterns was to make the emotions behind them as obvious as possible so that a user would be able to know what emotion a haptic pattern represented without being shown beforehand. Throughout our exploration, we made significant progress in building patterns that were more universally recognizable but were unable to come up with a final, definitive pattern for each emotion.

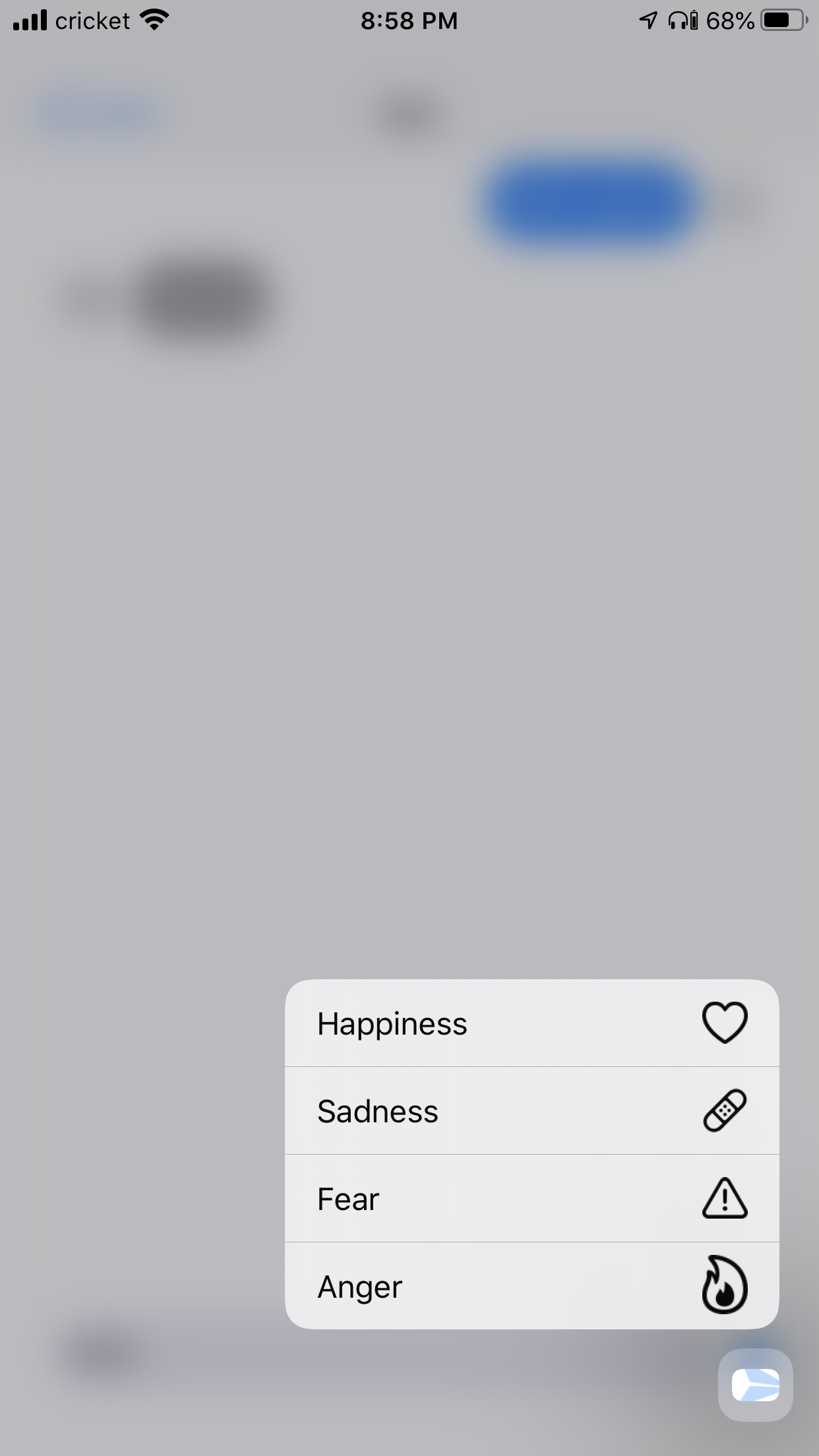

One piece of feedback received many times throughout the development of these emotional patterns was that implementing six different emotions made it more difficult for each pattern to be memorable and distinct from one another. Because of this, we changed the number of ’Haptic Emojis’ from six to four, as research has been conducted that considers only four basic human emotions [9]. To do this, we removed surprise and disgust, as it has been suggested that these two emotions are simply types of fear and anger, respectively. Thus, we were left with 4 Haptic Emojis which were implemented in Touchy Feely, anger, fear, sadness, and happiness.

The interface to send one of four "haptic emojis"

Within the Touchy Feely app, the user was able to send a text message with a Haptic Emoji by long pressing on the send icon and selecting one of the emojis from the submenu. Messages could be sent with either one or zero Haptic Emojis, and the Haptic Emoji specified would be played on the user’s phone when they opened and viewed the message.

Evaluation

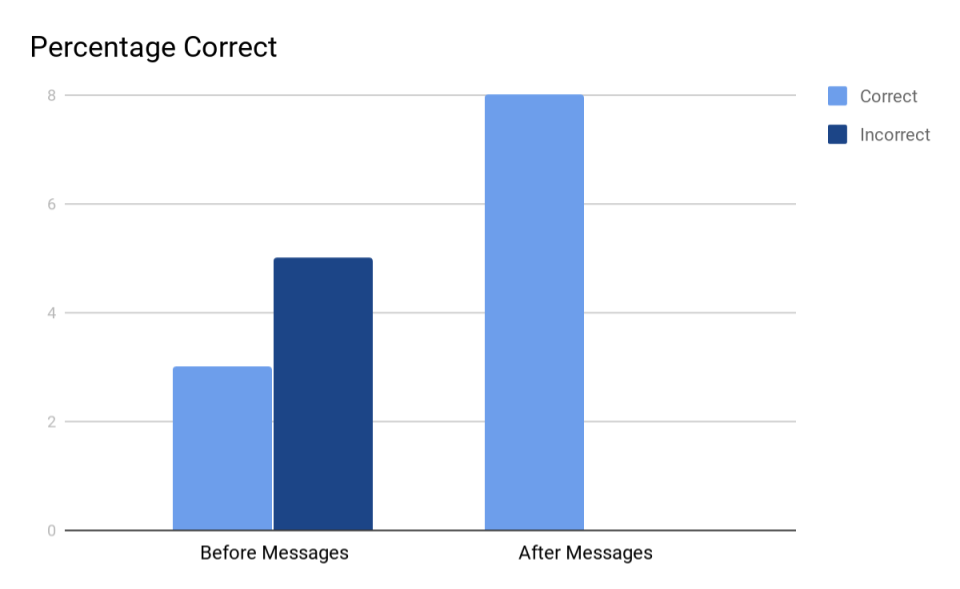

The three things we wanted to measure in order to answer our research question were how well the users understood the meaning of the Haptic Emojis, whether the Haptic Emojis allowed for a greater emotional understanding, and whether it was possible for users be taught which haptic patterns represent which emojis. To find answers to these questions, we set up a user experiment with a small group of participants. These experiments were conducted with the participants’ full understanding and consent, and they were aware of how their information would be used in this study.

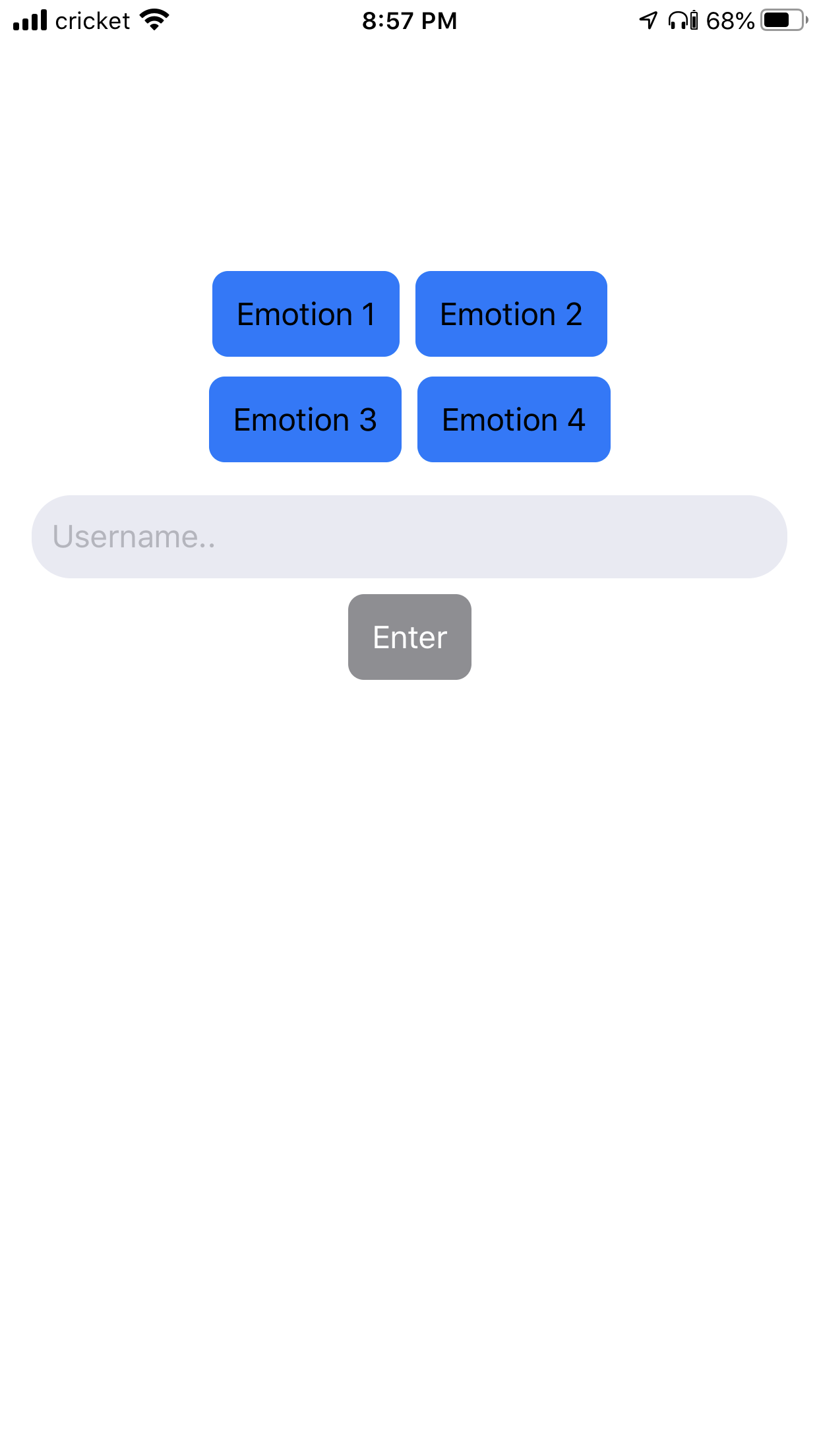

The first phase of this study was to introduce the participant to the concept of Haptic Emojis, and asses their initial understanding of the four different haptic patterns. On the home screen of the Touchy Feely app, the participant was presented with four unlabeled buttons, each of which corresponded to a different participant emoji. The participant was asked to infer which of the four emotions each button represented, and justify their reasoning.

The second phase of the study was meant to ’teach’ the participants the meaning of the four different Haptic Emojis. The study administrator sent eight different messages with Haptic Emojis (two per distinct emoji), while the participant read the texts and felt the vibrotactile pattern through the phone in their hand. For example, one such message was ”I haven’t seen my friends in months”, which was sent with the sadness Haptic Emoji. These messages were not meant to be overtly representative of the emotion which they were supposed to convey, but instead were supposed to be clear enough to suggest which haptic emoji they represented, but also vague enough that the haptic emoji could provide some clarification to the intention of the message.

The final phase of the study was to repeat the test administered in phase one of the study, and note any changes in response from the first time the user interacted with the four buttons.

Results

Two distinct and interesting results emerged from this study. First was the interpretation of the different emotions as haptic patterns, and the second was of the effectiveness of the Touchy Feely application to allow for greater emotional understanding of text messages.

Interpretation of Haptic Emojis

In the first part of the experiment, users were usually only able to identify one or two out of the four haptic emojis correctly. The happiness Emoji was most commonly mistaken for fear. Multiple users noted that the emoji reminded them of a heartbeat, due to the pattern of two beats spaced closely together. One users stated that the heartbeat reminded them of the increased heartbeat that occurs when you are in a fight or flight situation. The sadness Emoji was identified correctly nearly every time, with participants using words such as ”mellow”, ”subdued”, and ”sigh” to describe the haptic pattern. Fear was often mistaken for anger or happiness. One user stated that it reminded them of ”fists pounding on a door” while another said the pattern was reminiscent of clapping. Anger was mistaken once for happiness, but most users noted that the pattern felt like a low growl.

The home screen of "Touchy Feely"

Overall, these observations showed us that the haptic patterns could be interpreted in a variety of ways. Most of the interpretations came from references to real-life vibrations, such as heartbeats, laughter, or growling, rather than more abstract concepts behind emotions. However, all of the participants agreed that the four patterns were distinct, although they other disagreed on both the emotion represented by the haptic pattern, as well as the reasoning why. Because of this, it is clear that haptics that clearly represent common real-life sounds and other physical vibrations work best to allow participants to make a connection between the haptic patterns and the emotions that they represent.

After study participants were exposed to only eight different text messages with haptic emojis, they were able to associate the haptic pattern with the correct emotion 100% of the time. This shows that even with very little instruction or any explicit references to the four emotions, users were able to very quickly learn the meaning of the Haptic Emojis. This is important because as we saw with the initial experiment, there can be many different interpretations of haptic patterns, which means it would be very difficult to craft a Haptic Emoji that can be instantly identified by 100% of users. With this finding, we show that the meaning is something that can be quickly and unobtrusively taught to users while they use the app.

Below are the four different Haptic Emojis and the descriptions that participants gave to explain how the patterns made them feel.

| Happiness |

|---|

| It reminds me of a heartbeat in a stressful situation |

| Feels like when you’re afraid and your heart beats faster |

| It sounds like it’s trying to get your attention |

| Sounds like someone tapping you on the shoulder |

| It sounds like a heartbeat |

| Sadness |

|---|

| Seems like a mellow, toned down feel |

| It feels like a sigh |

| Seems sad |

| It seems like someone saying ”ew” |

| It’s the slowest one |

| Fear |

|---|

| Reminds me of someone pounding fists on door |

| Feels like laughing or clapping |

| Feels like someone laughing |

| Feels like someone laughing |

| Feels more upbeat than the others |

| Anger |

|---|

| It felt like a buzz, and when I am buzzed I feel happy |

| Imagine someone growling |

| It sounds menacing |

| It sounds like a low scary noise |

| It sounds like someone saying ”ta-daa” |

Effectiveness of Application

All of the users involved in the study agreed that the Haptic Emojis helped them better understand the intention behind the text messages. Participants stated that the Emojis served to re-emphasize the sentiment in the text and that while the tone was somewhat clear in from the text of the message, the emoji helped to confirm tone. Users also noted that the user interface was easy to use and understand and that the haptic patterns were enjoyable to use and interact with. This is important because if the Haptic Emojis are a feature that is appealing to users, it will be one that they are more likely to use when messaging with the app.

The home screen of "Touchy Feely"

Discussion

Based on our results, we were able to see that participants reported a higher level of understanding while messaging using Touchy Feely, which was the aim of our application. In addition, users also reported that user interface was appealing and intuitive to use, which means that the application has potential to be implemented on a much wider scale. Distribution of an iPhone app via the Apple App Store is relatively simple to do, and positive user feedback would lead to higher number of downloads and active users.

While the goals of the project were accomplished, naturally, there is much room for improvement and design decisions of our application that can be discussed. The biggest problem with this study is the lack of users. Due to the ongoing Covid-19 situation, we were unable to conduct interviews safely with people who did not reside with us. This meant that although we believe that Touchy Feely could have important implications for those with impaired emotional perception, we were unable to test the application with participants who met that description. This led to a very small sample size, although the structure of this experiment allows for repeatability, and in the future, this experiment could possibly be done on a much wider scale.

Similarly, a higher number of participants would have allowed for a better initial design of the Haptic Emoji patterns. Although we did have a scientific basis for our initial design of the emojis, we found that being able to iterate upon these patterns with user feedback was invaluable to designing haptic patterns that more closely approached a universal level of understanding. Future work could include refining these haptic patterns to accommodate the viewpoints of a more diverse set of people than we were able to in this study.

There also exist many limitations with both the Touchy Feely application, as well as the iPhone hardware it was run on. In order for a user to be able to feel the Haptic Emoji, the user must be holding the device in their hands, which is not always the preferred way for users to read their messages. While this problem could be solved with a device such as a haptic belt, which was discussed in this paper’s background, that solution requires a greater adaption by the user and poses a higher barrier of entry. A high percentage of people already carry a smartphone with them in their day to day life, while few own a haptic belt, and the cost and novelty of such a device would be unappealing to many users.

As far as the application itself, Touchy Feely is currently lacking many of the features that would be available in a user-ready version. Some features would include replaying of Haptic Patterns, lock-screen notifications of new messages, and the ability to create new user groups. These features were excluded due to a lack of time to make the app fully-featured, but if this app were to be deployed on a larger scale, these features could be added without a substantial reworking of the codebase.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Touchy Feely has shown the potential that haptic technology holds for instant messaging apps, potentially allowing users to clearly express the intention behind their texts in an unobtrusive manner. Although many more study participants would be needed to definitively quantify how much of an impact these Haptic Emojis make, we were able to satisfy our original research question of the feasibility of whether haptic feedback could be used to enhance emotional understanding in instant messaging. In addition, we were able to gain insight into the many different ways in which users can interpret haptic patterns and some of the methods with which researchers can design haptic patterns to better mimic human emotions.

REFERENCES

- Core haptics. https://developer.apple. com/documentation/corehaptics.

- Firestore. https://firebase.google.com/docs/firestore.

- Swift ui. https: //developer.apple.com/xcode/swiftui/.

- T. Amsel. An urban legend called: “the 7/38/55 ratio rule”. European Polygraph, 13:95–99, 06 2019.

- L. Dey, M.-U. Asad, N. Afroz, and R. Nath. Emotion extraction from real time chat messenger. 05 2014.

- P. Ekman. What scientists who study emotion agree about. 1 2016.

- J. Hancock, C. Landrigan, and C. Silver. Expressing emotion in text-based communication. pages 929–932, 01 2007.

- J. Hertel, A. Schuetz, and C.-H. Lammers. Emotional intelligence and mental disorder. Journal of clinical psychology, 65:942–54, 09 2009.

- T. Indersmitten and R. Gur. Emotion processing in chimeric faces: Hemispheric asymmetries in expression and recognition of emotions. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 23:3820–5, 06 2003.

- K. Subramanian. Technology and transformation in communication. Volume 5:August 2018, 05 2018.

- D. Tsetserukou, A. Neviarouskaya, H. Prendinger, N. Kawakami, M. Ishizuka, and S. Tachi. ifeel im! emotion enhancing garment for communication in affect sensitive instant messenger. pages 628–637, 07 2009.

- H. Wang, H. Prendinger, and T. Igarashi. Communicating emotions in online chat using physiological sensors and animated text. pages 1171–1174, 01 2004.